Writers of historical fiction use past events and people to create a narrative story that is entertaining for the general public. Some use this as a biographical tool to show readers what life was like for a famous historical figure. One example is the Boleyn series by Philippa Gregory. Others use events as a backdrop, but do not include historical characters except as occasional cameos. Diana Gabaldon's Outlander series is a good example of this. A third kind of historical fiction is the 'what if' type. This category takes real events and people and says what if this happened instead? This is often called historical fantasy. In this realm lives time travel, magic, and alternate history. Diana Gabaldon's Outlander series falls into this last category as well for the time travel element. Harry Turtledove is known for his alternate histories which ask questions of a military nature. Would the civil war have been different if fought with WWII weapons? The obvious answer is yes, but how would it have been different?

When writing a historical fiction novel the first question a writer must ask is when will it take place? Next is where. Will the characters be involved in an event? Does this involve traveling? How much do you know about this time period and its culture? How much research might be involved? How true to history do you wish to stay, or would you rather take artistic license in order for history to fit your story? Answering these questions will help you as you get started, but you may need to revisit a few as you write. Everyone has a different writing process. For many the story is created start to finish in an outline with characters and events in their basic form and then details fleshed out in the first draft. For others the creative process is wholly organic and the story seems to create itself.

The consistent piece of advice that every writer has every given any aspiring writer is this: Write, often. It doesn't matter what you write, just do it. To that end I have taken their advice. When I get stuck on one story I switch to another, or to this blog. Just so long as I write something everyday. Keep reading, keep writing, keep growing, keep learning.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Bias in History

No matter how hard a historian might try to distance themselves from their personal history and and approach a subject without bias, it is virtually impossible to do successfully. It is this reason that most historians appear dry and dull to those they are trying to teach and it is only recently that many have decided to abandon this practice in favor of a new more alive history that accepts bias and tries not to ignore it but rather to understand it.

In the first manner the approach to the middle ages would have been dry facts and figures that shied away from cultural impressions because the historian could not control their bias in a discourse of supposition. In the new manner a historian would discuss the basics of lifestyle that would shape an individuals thoughts and use their own experiences and the examples found in primary sources to form the basis for their theories. For example, it was often believed that women in the middle ages were in a similar state of male domination as their Victorian counterparts. It is true that most of documented history supports this, but it seems they had much more freedom than was previously believed. Although they were often in the minority and sometimes lesser than their male counterparts, there were women artisans, writers, theologians, and rulers.

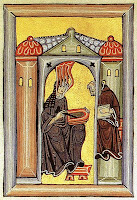

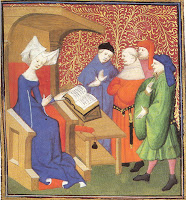

Here are some primary sources to support this. (A primary source is any document, art, or other first hand account that is from the time period being studied.) Christine de Pizan (1364-1430) is often viewed as Europe's first professional female writer. She was the court writer for several French courts including Charles VI. Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was a German writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, and Benedictine abbess. Margaret I of Denmark ruled Denmark in her own right and through her marriage to King Haakon VI of Norway and Sweden established the Kalmar Union which united the Scandinavian countries for over a decade. Below are depictions of Christine de Pizan and Hildegard of Bingen from illuminated manuscripts.

Monday, August 26, 2013

Historiography

The study of history itself comes in many disciplines. Every field of study from art to science has a history and each its own unique view point. There are also several theories about history and how it is shaped that influence how historians study the subject. The two main theories that most people use, are the Great Man theory and the Great Events theory. The great man theory holds that history is moved by individuals and leaders. The great events theory suggests the opposite in that the events shape the people. There is a third theory that has recently grown in popularity that combines the two in a cultural theory, that events and people shape each other. This third form of study focuses more on the how and why of history and less on the facts of what.

For the my focus on 12th and 13th century Western Europe the use of these theories is helpful in creating a picture of life in those times. Cultural studies start at the bottom with the lowest classes asking questions about daily life. What did they eat and wear? What did their houses look like and what did they do for work? As you move through each level of society you recreate the whole picture with no missing pieces. Did they go to school? What was worship like? Events studies creates a time line that holds each society together. Were there wars, rebellions? Who was allied to who? Were they allied through marriage, treaties, did the alliance last? In the study of great men/women we follow the lives of kings and queens, popes and heretics, scientists and philosophers, artists and rebels. These are the people who were in the right place at the right time to effect a change in their societies that had a lasting impact. Had they lived earlier or later things might have been different for them, but we can only speculate on the might have beens.

For more information on historiography and other views on the study of history check out Michael Bentley's Modern Historiography: An Introduction.

For the my focus on 12th and 13th century Western Europe the use of these theories is helpful in creating a picture of life in those times. Cultural studies start at the bottom with the lowest classes asking questions about daily life. What did they eat and wear? What did their houses look like and what did they do for work? As you move through each level of society you recreate the whole picture with no missing pieces. Did they go to school? What was worship like? Events studies creates a time line that holds each society together. Were there wars, rebellions? Who was allied to who? Were they allied through marriage, treaties, did the alliance last? In the study of great men/women we follow the lives of kings and queens, popes and heretics, scientists and philosophers, artists and rebels. These are the people who were in the right place at the right time to effect a change in their societies that had a lasting impact. Had they lived earlier or later things might have been different for them, but we can only speculate on the might have beens.

For more information on historiography and other views on the study of history check out Michael Bentley's Modern Historiography: An Introduction.

Friday, August 23, 2013

National Identity

The idea of nationalism is a fairly modern concept. In the middle ages boundaries were still heavily contested. Some areas under dispute were not settled until as recently as World War I, for instance Alsace-Lorraine between France and Germany. During the early middle ages the feudalistic form of government meant that loyalty belonged to the liege lord, not the land. Because land was constantly changing titles and boundaries it fell to the individual to be the leader around whom loyalty and devotion was owed. In later years as monarchies consolidated power, the average person identified with their local lord first. Even in our global world where cultural lines have begun to blur, regional differences still play a large part in our identities. This was more pronounced in the middle ages, where travel took longer and change was slower.

In France there were two main regional divides, and for the most part they still exist today. The northern region held the counties/dukedoms of Normandy, Brittany, Poitier, Berry, Burgundy, Champagne, Lorraine, Bourbon, and the most important Ille de France. These were collectively known as the Langues d'oil for the language pronunciation of the word yes, oui. The south is a smaller region and was referred to as Langues d'oc, there is an area that still is in fact. The majority of the south was controlled by the county of Toulouse. Also in the region were the counties of Aquitaine, Gascony, and Provence. Prior to the mid-1200s, this southern region was under the vassalage of the King of Aragon in what is now Spain. Being so close to the borders, Provence held close ties to both France and Italy. After the so-called Albigensian Crusade, these areas were brought under more direct control by the King of France.

Even the Holy Roman Empire consisted of a number of smaller regions joined under the Emperor. Much the same way the the European Union today is composed of individual countries united under a common council, each part is still largely autonomous although it is subject to the higher authority.

The Hundred Years War between France and England, beginning in the 14th century, was a territorial war over the right to the throne. There were very close ties between France and England after William the Conqueror of Normandy claimed the throne of England, and several subsequent marriage alliances between the two countries. The conflicts between the two countries helped to foster a sense of nationalism, especially with the arrival of Joan of Arc and her immense popularity even to this day.

The advent of the printing press in the mid 15th century and it's importance to the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation helped to increase this growing nationalist movement. The vernacular languages of each country began to be standardized during this period as regional differences were merged. The creation of a middle class during this time period also fostered less dependence on the ideology of nobility and liege-lords, and more of a connection to the idea of King and Country. Many factors went into this, but I will not delve into them at this point.

For more information on the rise of nationalism, try Henry Kamen's Early Modern European Society, or Elizabeth L. Eisenstein's The Printing Press as an Agent of Change.

In France there were two main regional divides, and for the most part they still exist today. The northern region held the counties/dukedoms of Normandy, Brittany, Poitier, Berry, Burgundy, Champagne, Lorraine, Bourbon, and the most important Ille de France. These were collectively known as the Langues d'oil for the language pronunciation of the word yes, oui. The south is a smaller region and was referred to as Langues d'oc, there is an area that still is in fact. The majority of the south was controlled by the county of Toulouse. Also in the region were the counties of Aquitaine, Gascony, and Provence. Prior to the mid-1200s, this southern region was under the vassalage of the King of Aragon in what is now Spain. Being so close to the borders, Provence held close ties to both France and Italy. After the so-called Albigensian Crusade, these areas were brought under more direct control by the King of France.

Even the Holy Roman Empire consisted of a number of smaller regions joined under the Emperor. Much the same way the the European Union today is composed of individual countries united under a common council, each part is still largely autonomous although it is subject to the higher authority.

The Hundred Years War between France and England, beginning in the 14th century, was a territorial war over the right to the throne. There were very close ties between France and England after William the Conqueror of Normandy claimed the throne of England, and several subsequent marriage alliances between the two countries. The conflicts between the two countries helped to foster a sense of nationalism, especially with the arrival of Joan of Arc and her immense popularity even to this day.

The advent of the printing press in the mid 15th century and it's importance to the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation helped to increase this growing nationalist movement. The vernacular languages of each country began to be standardized during this period as regional differences were merged. The creation of a middle class during this time period also fostered less dependence on the ideology of nobility and liege-lords, and more of a connection to the idea of King and Country. Many factors went into this, but I will not delve into them at this point.

For more information on the rise of nationalism, try Henry Kamen's Early Modern European Society, or Elizabeth L. Eisenstein's The Printing Press as an Agent of Change.

Sunday, August 4, 2013

Fashion in the Early Middle Ages

Every society has a set idea of what is considered acceptable fashion. Some are based more on function and have few set rules on style. Others, like the Victorian period, dictate very strict guide lines and requirements. The early middle ages in western Europe saw the Roman style mix with the up and coming Franks, Gauls, Saxons, and other tribes. The continent's climate was cooler then, so long layers and cloaks were practical. With the addition of Christianity, modesty in clothing also became more important. In Rome the typical fashion was the chiton, for men and women, it was essentially a sleeveless tunic gathered at the waist with a belt. It was worn in varying lengths, but as Rome's power fell, so to did it's hold over fashion. The tunic was still worn, but sleeves were added and the hems of women dropped to below the ankle.

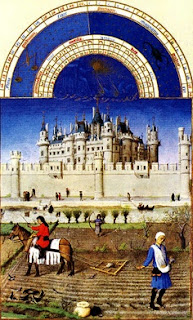

This simple drapery style held sway with many variants until the 14th century when styles began to change drastically. During this early period with Christian morals in sway, women began covering their hair in veils. For peasants these were simple linen coverings, but for the wealthy headdresses could be quite elaborate. Most clothing were made of linen or wool, but trade with the east, especially after the crusades, saw the import of silk and cotton. Fabric dyes would only be limited by nature and the imagination, so while many modern minds imagine peasants wearing only browns and natural colors, they are more likely to have had more colorful outfits similar to these depicted in the illuminated manuscript of the Duke Jean de Berry of France by the Limbourg brothers in the early 15th century.

The layering of a more elaborate overdress with a simpler underdress allowed for a more elaborate style while serving a very practical purpose. A plain linen underdress could be washed more frequently than embroidered gowns of heavy wool or trimmed fur dresses. In an age where water had to be heated over a fire and then carried by hand, it made sense to be as practical as possible. That does not mean they only bathed once a year. Even after the fall of Rome, their ideas of cleanliness still influenced western society.

The birth of the Italian Renaissance and its ideas on humanism broke some of the Church's power and with new trade and industry a middle class was formed. This class of wealthy tradesmen with aims of nobility could afford to dress like the nobles, so fashion began to be increasingly more intricate and ever changing in an attempt to differentiate the classes.

For more on historical fashion try these books.

Cosgrave, Bronwyn. The Complete History of Costume and Fashion: From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. New York: Checkmark Books, 2000.

Payne, Blanche, Geitel Winakor, and Jane Farrell-Beck. The History of Costume. 2nd ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Piponnier, Françoise, and Perrine Mane. Dress in the Middle Ages. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Wagner, Eduard, Zoroslava Drobná, and Jan Durdík. Medieval Costume, Armour, and Weapons. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2000.

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Pilgrimage and Crusade

With the rise of the Christian Church, a curious paradox between peace and violence was created that has spread to every corner western culture has touched. War and violence were very prevalent as lords and kingdoms fought to create new boundaries out of the chaos left by the Roman Empire's loss of power to the barbarian invaders. The Church tried to limit this by establishing the so-called Peace or Pax in Latin. During the conversion of the Romans and then the European continent, the priests spoke of Jesus' message of peace and self-sacrifice, but in a world were violence was often deemed necessary, a message of nonviolence was not going to be an easy sell. The concept of justified, or even holy, war was created out of the Christian message. It became God's will that the strong protect the weak, for the Bible says that the meek shall inherit the earth.

Pilgrimage was an established practice long before Christianity came on the scene, and there are many pilgrimage sites that are sacred to more than one religion. Jerusalem has always been the most controversial of such sites being the center for three of the worlds largest religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. All three religions hold pilgrimage to be important and believe that every man should travel to a holy site at least once in their lifetime. Although violence on the roads were still hazardous, Christian pilgrims carried outward signs of their journey that all but the most hardened criminals respected out of fear of Godly retribution. This safety of the road became an established Peace dictated by the Church and executed by the local political authority. It was also extended to include women, children and the clergy.

The first crusade was initially an appeal from the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Kommenos to Pope Urban II for military aid to protect his boarders against the Seljuq Turks in 1095 CE. Urban II saw this as a greater opportunity to reclaim the whole of Palestine and the Holy Land for Christendom. To that end he began a preaching campaign lasting most of a year calling for a military pilgrimage, a holy crusade. Over the following 200 years there were six major crusade expeditions, along with at least six minor expeditions, the so-called people's crusade, the children's crusade, and the crusades outside of the Holy Land including the Reconquista in Spain, the Albigensian in Southern France, the German crusade, and the Northern crusades against various pagan and heretical groups including Slavic minorities.

Ultimately the Europeans were unable to hold the lands they claimed in Palestine, but they were greatly influenced by their travels and brought back more than war stories. Expanded trade routes were set up bringing in silks and spices. Artisans and intellectuals discovered techniques and ideas lost in western Europe, but preserved in the Islamic and Greek east. Although the crusades were war driven, they also made travel easier, almost a Christian duty, and this allowed the 12th and 13th centuries to thrive in a way they had not since the fall of Rome. Universities were founded in Paris and elsewhere that were not directly connected to the church. Architecture rose to new heights as the Gothic style was created. The 12th century is sometimes called the little renaissance of the middle ages.

For more detail information on the crusades check out Christopher Tyerman's God's War: A New History of the Crusades

Ultimately the Europeans were unable to hold the lands they claimed in Palestine, but they were greatly influenced by their travels and brought back more than war stories. Expanded trade routes were set up bringing in silks and spices. Artisans and intellectuals discovered techniques and ideas lost in western Europe, but preserved in the Islamic and Greek east. Although the crusades were war driven, they also made travel easier, almost a Christian duty, and this allowed the 12th and 13th centuries to thrive in a way they had not since the fall of Rome. Universities were founded in Paris and elsewhere that were not directly connected to the church. Architecture rose to new heights as the Gothic style was created. The 12th century is sometimes called the little renaissance of the middle ages.

For more detail information on the crusades check out Christopher Tyerman's God's War: A New History of the Crusades

Friday, July 19, 2013

Architecture

One of the easiest ways to track the changing needs and temperaments of a time period is through the architecture. The middles ages are broken into several art periods. The early period is characterized by Byzantine and Islamic in the East, and a synthesis of late antiquity with northern traditions or the so-called barbarian invaders. With the rise of the church's influence, cathedrals and monasteries develop a style called Romanesque. These focus primarily in the 11th and 12th centuries and the term itself is a fairly recent innovation. Previously these buildings and sculptures were considered an early phase of Gothic, but are now regarded as a separate school of architecture. The late middle ages saw the rise of Gothic art, beginning first in France in the late 12th century then spreading out with distinctive regional differences to the basic style.

The other major form of architecture during the middle ages took the form of castles and manor houses. After the fall of Rome most of Europe went through a violent age of power struggles. Many retreated behind high walls and thick fortifications. As kingdoms were created and things became more peaceful, villages became cities and castles became palaces.

Check the links for some sites that list famous castles and cathedrals.

The other major form of architecture during the middle ages took the form of castles and manor houses. After the fall of Rome most of Europe went through a violent age of power struggles. Many retreated behind high walls and thick fortifications. As kingdoms were created and things became more peaceful, villages became cities and castles became palaces.

Check the links for some sites that list famous castles and cathedrals.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

What are the middle ages?

It has become accepted in the academic world that the middle ages fall roughly between the years 476 CE and 1500 CE, beginning with the fall of Rome. The end date has been subjected to more controversy and generally depends upon ones area of study, or sometimes nationality, as to what event is used as the signal for the modern era. The term middle ages was an invention of of the Italian Renaissance when historians, like Leonardo Bruni in his 1442 History of the Florentine People, began dividing history into three eras rather than two. These became the Ancient, Middle, and Modern.

The middle ages has sometimes been called the age of ages, for it incorporates so many different culturally significant time periods that it cannot be defined by one overall theme. The decline of the Roman Empire left a power vacuum that allowed the rise of the Catholic Church in the west, and smaller empires in the east. Because the study of history is the study of insert topic here, historians often limit their focus. The main events when discussing the middle ages in Europe center around wars of politics and wars of religion, and sometimes it is difficult to separate the two.

My focus will primarily center in southern France, but will include any topic which would effect the people there. There will be posts on wars, religion, politics, art, and discourse on the variety of cultural differences that influenced daily life.

For more general information The History Guide is a great place to find lectures on every period in history.

The middle ages has sometimes been called the age of ages, for it incorporates so many different culturally significant time periods that it cannot be defined by one overall theme. The decline of the Roman Empire left a power vacuum that allowed the rise of the Catholic Church in the west, and smaller empires in the east. Because the study of history is the study of insert topic here, historians often limit their focus. The main events when discussing the middle ages in Europe center around wars of politics and wars of religion, and sometimes it is difficult to separate the two.

My focus will primarily center in southern France, but will include any topic which would effect the people there. There will be posts on wars, religion, politics, art, and discourse on the variety of cultural differences that influenced daily life.

For more general information The History Guide is a great place to find lectures on every period in history.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

What this blog is for...

I am creating this as an educational aside. It is in part to help with my research will I write my novel, and part to share my love of history. I will be focusing on the 12th and 13th centuries in my writing, but that does not mean I will limit this site to those couple hundred years. Geographically I will be emphasizing southern France, but like many of you may know or will learn, medieval Europe was much more internationally involved than the Victorian ideal of the peasant farmer who never traveled farther than 10 miles from his place of birth and knew little of the world outside his village.

My first several posts will deal with the general history and set the stage for further discussions. Topics will range from Kings and Popes, to the crusades and chivalry. I would love feedback, questions and comments. Enjoy!

My first several posts will deal with the general history and set the stage for further discussions. Topics will range from Kings and Popes, to the crusades and chivalry. I would love feedback, questions and comments. Enjoy!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)